26 November 2024

Navigate to:

EU Values Foresight Homepage

How European Democracies Are to Survive a New Trump Age – 2023 Report

Horizon Scanning

Events

The critical question for democracies today is how to wield their collective will and resources for a credible defence posture. For now, European democrats are primarily reactive and demobilised against mounting geopolitical pressures. This report presents perspectives on how the EU can safeguard democracies, based on the EU Values Foresight project conducted in four Central European countries.

The Democracy Defence Package proposal, published by the European Commission at the end of 2023, exacerbates this concern. For many years, disinformation schemes amplified across the West have eroded the fundamentals of democratic order, weaponising our trust and openness against us. The EU must take the initiative, not merely react, and build a vantage point. This position can only be derived from societal and economic power, thereby establishing a credible defence posture that enables the EU to become an effective foreign policy actor.

To dominate the EU’s political landscape, our adversaries seek to demoralise, divide and demobilise us. In response, Europe must reinforce its foundation of democratic ideals that ensure a robust defence stance.

The challenge lies in balancing international goals with domestic realities. Potential coping strategies of political actors that we have observed so far include scaling back international commitments, propelling nationalist sentiments built on appeasement or to the contrary – using geopolitical confrontation to rekindle Western solidarity, including an idea of a new social contract. For if all are to bear the burdens of defence posture they need to regard it as a fair arrangement to ensure the durability of the effort. It is not just what the EU can do, but how it can empower EU citizens to do more in a sense of duty for their collective rights and freedoms.

Thus the report discusses four strategies for navigating the current geopolitical landscape that are important for a combined investment in democratic values and defence. They bear relevance primarily for the new

upcoming policy initiatives like the European Democracy Shield, the Democracy Defence Package, the Niinistö Report on Civilian and Military Preparedness and the upcoming White Paper on the future of European defence. It also addresses the challenges faced by civil society, especially in at-risk democracies.

Thinking along two axis of geopolitical hard power and the power of democratic norms and trade there are naturally emerging four scenarios:

• Globalist Europe Scenario: A globalist approach focused on economic prosperity, which risks marginalisation in global affairs and exploitation by populist factions

• Isolationist Europe Scenario: An isolationist approach withdrawing from previous commitments, favouring de-conflicting strategies and potentially leading to long-term dependencies on autocratic regimes.

• Nationalist Europe Scenario: A nationalist approach prioritising national sovereignty, undermining the EU’s institutional framework and potentially diminishing personal freedoms and security.

A fourth and final strategy, the Europe Power Scenario, focused on enhancing military capabilities and societal resilience, is presented as the most effective way to contribute to peace-building and security on the continent. This involves utilising existing structures to bolster armies, fund military industries and instil a sense of protection against the spillover of military tensions.

Click here to download the pdf

In the next five years, some political actors will promote the European Union’s globalist agenda, promising a return to an age of evergreen prosperity while ignoring

present and future security challenges. Should Europe follow their lead and continue to adapt the globalist agenda to new challenges, it risks marginalisation in global affairs. Additionally, this approach brings the risk that anti-globalist populist far-right and far-left factions will exploit the EU institutions’ and democracies’ weaknesses in delivering a sense of security and control.

The inefficiency of the ‘Brussels bubble’ and mainstream parties in mastering crisis situations and their reactive approach to risks will also be highlighted by these factions. By the 2029 European Parliament elections, fringe groups could dominate, potentially paralysing the EU completely.

‘Run the state like a business’ is the main electoral slogan of Andrej Babiš, a Czech oligarch and politician who might again become the prime minister after the 2025 general elections. During his previous cabinet, Czechia saw stable economic growth and the lowest unemployment rate of 2.02% in 2019 – an object of envy across the EU and the world. The metaphor of business-first approach aligns with the strategy pursued by the EU until recently.

Over the past decades, the mercantile philosophy of peaceful global transformation of political tensions has brought unprecedented prosperity to the EU. Built on the traumas of the World Wars and the collapse of imperialist ambitions, the EU believed that ‘never again’ was not merely an ambition but a reality, confirmed by the 1989 democratic transition, the implosion of the USSR and the peaceful integration of Eastern European countries. The tragedies of the Balkan wars and the Middle East, let alone Russian ‘special operations’, were treated as mere hiccups of the past, while the economy-driven agenda dominated policy planning.

A series of crises, from post-enlargement reshuffles to financial and pandemic shake-ups, never upset the EU’s optimism. The EU was seen as a well-balanced, slowly growing economic sphere that could impose its rules globally due to its stake in value chains and consumer power. Wars and the politics behind them were perceived as remnants of a collapsed world, with an everlasting optimism that economic interests would universally prevail.

This mindset fostered the belief that prioritising economic interests over defence or security strategies was justified, as things would eventually stabilise. For Czechia’s former PM, this approach necessitated political alliances with radicals — nationalists and communists from the fringes. Adhering to a business- as-usual strategy amid global risks and uncertainties led to mismanagement during major disruptions like COVID-19, ultimately resulting in Mr. Babiš losing two elections.

Similarly, the EU might hope that the Russian invasion of Ukraine will lose momentum within the next five years and that, despite historical evidence, there won’t be another, potentially greater conflict in the future. Consequently, a more ambitious plan to emphasise the security dimension of European integration may be sidelined in favour of maximising short to medium-term economic gains to sustain the economy. Even more importantly, actions that build up democratic security through policies on resilience or against foreign influence will largely remain paper tigers, because the economic costs of their implementation would be too much to bear for such a political mindset at the helm of the EU.

During this term, the EU might be tempted by a cave-in strategy that withdraws from its previous policies. An example of this trajectory is Slovakia’s shift

from engagement to isolationist policies since the 2023 elections, marked by a turn from a centre-right to a leftist government. This government pursues policies on Russia that align with many other leftist political groups across the EU.

Under the previous coalition government, Bratislava was the first EU and NATO country to deliver anti-air systems to Ukraine in 2022. Despite its limited military capabilities, Slovakia maximised its foreign policy impact. However, it struggled economically and has not regained its pre-pandemic economic vigour. The impact of global tensions on the EU’s economic competitiveness hit Slovakia hard, given it trades primarily with its closest EU neighbours – particularly with Germany (which accounts for 20% of Slovakia’s trade) and other Visegrad Group economies (27% of total exports).

Slovakia’s Prime Minister Robert Fico has called for a return to a policy of avoiding ‘superpower conflicts’. This strategic mindset may influence other EU countries, affecting overall EU performance. Traditionally, Slovaks have one of the friendliest attitudes towards Russia and the Kremlin’s policy. Despite being part of the Western alliance, a significant portion of the Slovak population is sceptical about NATO and the US. This relationship with Russia is rooted in historical gratitude for saving Slovakia from Hungarian domination in the 19th century and the Soviet army’s liberation of Slovakia.

Fico’s government has adopted policies that pull Slovakia out of big conflicts and commitments, reducing exposure to criticism from both Western partners in the EU and Eastern powers like China and Russia. Slovakia’s economic dependency on the German automotive industry leads it to favour de-conflicting strategies regarding China. Meanwhile, the government continues to undermine judicial, media and civil society environments but is constrained by its dependency on EU funding and rule of law conditionality. Fico has threatened to block support for Ukraine and complicate administrative and logistical efforts to deliver effective support to Kyiv should EU funds be limited due to his drastic policy initiatives that undercut the rule of law.

This isolationist approach, if adopted more broadly across the EU, could lead to a resignation from economic revival efforts and the abandonment of ambitious economic agendas. Instead, there might be a push to restore old trade relationships with Russia or China, which could offer economic patronage and political support, leading to long-term dependencies on their fossil fuels or manufacturing.

A resignation from global competition for security could be bolstered by unfavourable views of the US’s bold economic and military posture against China’s global ambitions. Staying neutral in these conflicts would equate autocratic and democratic systems of values, making it increasingly difficult for the EU to pursue its agenda of shielding European democracies from foreign or domestic malign influences.

The once potent ‘Europe of Nations’ concept proposed by Charles de Gaulle, who stood against a supranational European federation, has become a distorted reflection for nationalist forces seeking to undo European integration and increase the already strong intergovernmental format of decision making. The development of their agenda as the dominant strategy in Europe represents a mortal danger for the EU, as they aim to replace the innovative political framework with a failed model of freely competing nations. As the EU countries must upscale their military and policing powers due to external pressures, the nationalists – currently non-violent – would at a later stage take advantage of the power instruments while trumping the democratic partnership dimension of political space.

Ignoring past experiences where modern European cooperation failed against global powers, present-day nationalist forces risk undermining their own foundations. Should they succeed, European citizens’ personal freedoms and security would be diminished, leaving a hollow framework of values and rights without obligations.

Nationalist movements today aim to weaken the EU’s institutional framework, which limits their drive for centralised control within member states. A key proponent is Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán, whose political group, ‘Patriots for Europe’, is now the third-largest in the European Parliament. This group advocates for diminishing democratic partnerships and promoting a ‘might makes right’ approach both domestically and internationally.

This movement’s initiatives are often copied across Europe, like Poland’s PiS which mirrored Orbán’s policies. Future moves may include measures like Hungary’s 2023 Office for the Protection of Sovereignty, which targets organisations, journalists and NGOs seen as threats to ‘national sovereignty’, discrediting them through propaganda and exploiting vague legal frameworks. Short-term EU measures have yet to show impact.

Such policy initiatives pose formal obstacles to the candidacy of new member states like Georgia, effectively halting the EU enlargement process, which serves the nationalist agenda. Ignoring these measures and allowing new member states with similar policies would be risky but could be managed with an increasing toolbox of conditionality mechanisms and legal options under the EU Court of Justice.

Orbán positions himself as a leader of the anti-globalist protest against the mainstream, frequently referencing other strongmen who exploit existing international frameworks to maximise control over their societies and influence other nations and institutions. As Orbán stated, ‘What we see is that there is an elite made up of the left, the liberals and the centre-right, called the mainstream, which runs things. But the European mainstream is surrounded by a ring of protest because the European people do not agree with their actions.’

The nationalist agenda in Europe appears weaker and non-violent, but the far-right emphasises anti- immigration, welfare chauvinism, and harsh legal measures. These factors could lead to increased societal and international tension as they gain political traction.

Nationalists glorify vague notions of sovereignty and push for national parliaments to veto EU legislation, weakening the European Parliament’s powers. This approach raises concerns about rights and freedoms being undermined by nationalist agendas at the national and local levels.

This scenario underscores the risks of a nationalist Europe, highlighting the need for a balanced approach to democratic security. The EU must confront these movements and their impact on European integration to maintain stability, security and protect personal freedoms and rights.

In the next five years, if the EU maintains its current course and utilises its resources to enhance military capabilities and societal resilience, it will significantly contribute to peace-building and security on the continent. This effort is less about creating new legal frameworks and more about political leadership finding the courage to use existing structures to bolster armies with personnel and equipment, fund military industries and instil a sense of protection against the economic and moral spillover of military tensions.

The European Union has accelerated its efforts to upgrade its defence posture. Both member states and EU institutions are preparing white papers on defence capabilities and developing a European democracy shield toolbox to reinforce societal resilience against autocratic operations aimed at undermining morale. Military theorists emphasise that both moral and material forces are crucial for building power.

Multiple voices suggest that Europe faces its most critical moment since the end of the Second World War and must prepare to defend itself. Polish Prime Minister Donald Tusk emphasises the need for NATO countries to meet the 2% GDP defence spending target and increase aid to Ukraine to prevent pessimistic scenarios. Poland plans to spend over 4.5% of its GDP on defence in 2025, with most eastern flank countries meeting or exceeding the 2% NATO pledge. Tusk highlights the unpredictability of the current situation, stating that ‘literally any scenario is possible’, and stresses the importance of mental readiness for this new era. He also notes the shift in European leaders’ attitudes towards recognising the threat posed by Russia, a concern long voiced by Central and Eastern European countries.

Vladimír Špidla, former Prime Minister of Czechia and EU Commissioner for Employment, Social Affairs and Equal Opportunities (2004-2010), remarked in an interview, ‘The postwar order is broken, and the Union must change too. The balance of power has returned to the world, meaning a concert of global powers. We must be at the table, or we risk being the losers. The Union must consider what actions to take to be part of this concert of global powers. It does not need to be a superpower, but it must be a power.’

The sources of EU power are neither limitless nor as potent as those of the US or China. However, they have not been fully harnessed and coordinated to maximise efficiency. Should a coalition of willing member states maintain a steady course towards enhancing Europe’s power, the effect would be a chilling deterrent to foreign adversaries and help pacify domestic populist radicals. Ukraine, which was not expected to withstand the pressure of a mighty aggressor like Russia, has achieved numerous successes in battles that have effectively contained the invasion. These achievements have been made with a fraction of European resources and political capital.

What Europe can achieve to reinstate a sense of peace and security on the continent by building partnerships and enhancing its own power would undoubtedly deter, if not dwarf, the capabilities of Western opponents in both moral and material terms. This scenario underscores the importance of a balanced approach to strengthening Europe’s defence and societal resilience to meet the challenges of the pre-war era.

The globalist strategy, pursued successfully over past decades has exploited its potential for delivering security and prosperity in Europe. The Union is now at a critical juncture. Having the analytical ability to map out its options and design a course of action, Europe must also be bold and its leaders take pivotal decisions.

This scenario-based framework outlines policy options aimed at achieving a democratic and powerful Europe that upholds liberal international order principles. It emphasises the interconnectedness of domestic and international policies, recognising that a strong and cohesive society is the foundation for international cooperation and influence. The following recommendations are not the only ones but they are certainly the hottest issues to deal with in the proposed framework.

This policy report is accompanied by three policy briefs prepared on the basis of strategic foresight workshops with civil society actors across Visegrad Group countries of the EU and ongoing horizon scanning of democratic security trends and developments across all eastern European member states.

The author of the first policy brief, Magdalena Jakubowska, recommends that the EU audit the current human resources of the member states’ armies, revise conscription models to increase the number of soldiers ready for the battlefield, increase female involvement in the military, direct CERV programming to include pro-defence CSOs, emphasise that defence is a common good for the EU, and ensure that army training includes civic education in line with EU values.

The rationale for these recommendations is that despite the looming threat of war, the EU’s preparedness needs improvement. The current state of trained military personnel is poor, alongside demographic decline, low female participation and limited civic education.

In the second policy brief, Marzenna Guz-Vetter recommends that the EU makes it easier for CSOs to apply for grants, ring-fence a pool of grants for CSOs, improve contact points for CSOs to access EU funds, allocate part of the budget of European Commission Representations in Member States for grants to CSOs, increase operational funding that is not project-based, speed up work on the European Civil Society Strategy, include CSOs more in the work of the European Commission on strengthening and defending democracy, include country-specific data on the use of EU funds by CSOs in the EC’s annual Rule of Law reports and have CSOs organise more experience-sharing and critical evaluation of CERV mechanisms.

The rationale behind these recommendations is that CSOs in countries with autocratic tendencies face barriers to accessing EU funds, limiting their participation in European governance.

Galan Dall’s policy brief recommends that the EU broaden its approach to malign foreign influence to include domestic actors, funding communication campaigns to promote CSOs, increasing EU budgets for CSOs, enshrining legal protection for pro-democracy CSOs, establishing a legal defence fund for lawyers aiding CSOs, adapting the Erasmus+ programme to support trainees and interns at pro-democracy CSOs and coordinating EU-wide media literacy efforts.

The rationale for these recommendations is that the EU’s current approach to countering malign influence focuses on foreign agents, overlooking domestic actors perpetuating disinformation. This leaves CSOs vulnerable to pressure from their own non-democratic governments.

• Democratic Participation: Encourage broader participation in the democratic process, including through initiatives to increase voter turnout and promote political education. Explore innovative approaches to citizen engagement, such as deliberative democracy platforms.

• Military Service: Revisit the debate on mandatory military service, considering its potential benefits for fostering social cohesion, promoting civic responsibility and strengthening national defence. Address concerns about inclusivity and ensure equal opportunities for participation.

• EU Leadership: The EU should take a leading role in promoting liberal internationalist values and strengthening multilateral institutions. This includes actively engaging in global efforts to address climate change, promote human rights and resolve conflicts peacefully.

Achieving a democratic and powerful Europe requires a comprehensive and integrated approach that strengthens society at home while fostering greater cooperation abroad. By prioritising social cohesion, investing in crisis response capabilities, promoting economic growth and leveraging synergies between domestic and defence policies, Europe can assert its place as one of the leading global powers. Failure to stand up to the challenge would only fuel nationalist or isolationist agendas and lead to an implosion of the European project.

Can the EU frame its collective defence posture as a public good? While EU citizens benefit from a robust framework of freedoms, the only reference to EU citizens’ obligations can be found in the Charter on Fundamental Rights of the EU, where the preamble reads: ‘Enjoyment of these rights entails responsibilities and duties with regard to other persons, to the human community and to future generations.’ Accordingly, the Treaty on the European Union calls on Member States to provide military and civilian capabilities (Article 42.3). It also calls for the progressive framing of a common Union defence policy (Article 42.2).

With the peace dividend in Central Europe no longer guaranteed, nations are providing economic and military aid to Ukraine to prevent similar threats to themselves. They are also bolstering defence capabilities by increasing budgets, purchasing equipment and reviving production of military supplies.

However, security remains a largely national concern. This is even though urging the EU to take defensive action will only be sufficient if defence is seen as a shared responsibility and necessary protection of shared EU values. It is also increasingly clear that military readiness will require human resources.

Conscription offers Central Europe not just the chance to become more militarily resilient but also to develop its democracies by aligning member-state armies with shared EU values. The question is whether EU citizens are willing to take on this duty and perceive defence as a common good and to what extent they are encouraged to do so.

Memories of Central Europe’s violent past remain strong. The events of World War II in 1939, the 1944 uprising in Poland and the subsequent years of communist terror – such as the 1956 uprising in Hungary and the 1968 Prague Spring in Czechoslovakia – are vivid reminders of times of conflict. Perception of war threats is consequently high. Although this discussion is not yet mainstream, countries are beginning to strategise on how to expand their armies, or at least increase training and numbers of reservist troops.

Yet, military numbers remain insufficient. Conscription was suspended in these post-communist countries in the early 2000s: 2004 for Hungary, 2005 for Czechia and Slovakia and 2010 for Poland. Now, the state of trained military personnel is poor – on account of demographic decline, low female participation in the military and limited civic education. Central Europe accounts for not more than 350,000 soldiers or reservists – compared to Ukraine, which fields 800,000 on its own. This includes 216,000 personnel in Poland (the largest army in Europe, and 0.56% of the total population), 30,000 in Czechia (0.27%), 21,000 in Hungary (0.22%) and 16,000 in Slovakia (0.28%).

Initiatives to expand armies in the Visegrád Group are on the rise. In a rare show of bipartisan support, the Homeland Defence Act of March 2022 set a target of doubling the size of Poland’s armed forces to 300,000. In the first six months of 2023, Slovakia saw 215 more applicants compared to 2022. But such initiatives also face difficulties. Czechia’s KVAČR 2030 plan calls for 2,400 new recruits annually, but only 1,600 new soldiers joined in 2022, resulting in a net gain of just over 200 due to turnover. Hungary is doubling its defence efforts through the Zrinyi programme and plans to grow the army by 30%, to include 37,000 active personnel. Its first steps, however, involved a mass layoff of experienced officers, which critics see as an opportunity to enlist primarily party loyalists.

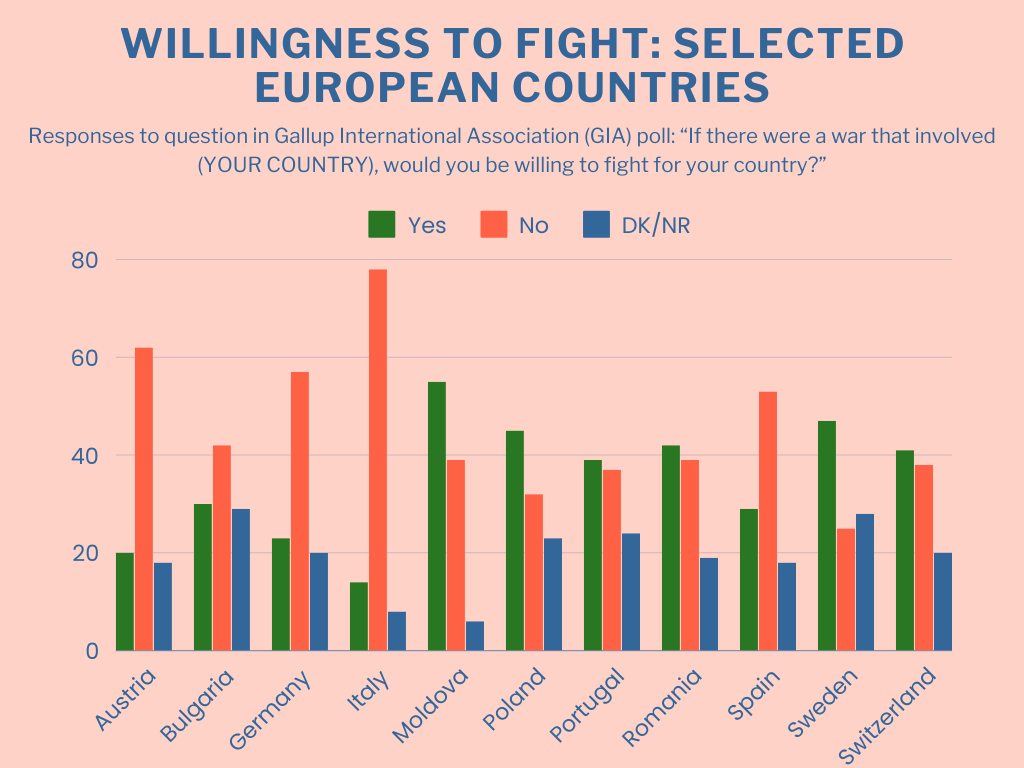

Willingness to fight is also lacking. Latest polls show that an average of 32% of citizens of Member States would be ready to go to battle. This rises to 40% in Central and Eastern European nations – in fact, four out of five countries whose citizens are least willing to fight are in Western Europe: Spain (29%), Austria (23%), Germany (20%) and Italy (14%). Yet, CEE attitudes also range significantly from countries like Bulgaria (30%) to Romania (42%), Poland (46%) and Moldova (55%). Hungary has seen a sharp increase in the number unwilling to fight, from 45% in 2022 to 63% in 2024. Reasons for reluctance vary by national context, but data from Hungary can be attributed to Victor Orbán’s ‘appeasement ideology’ as a key pre-election tool – encouraging citizens not to fight in a manipulation of the Hungarian historical tradition of 1848 or 1956.

Comprehensive data analysis reveals a positive correlation between conscription and citizens’ willingness to fight, a trend consistently supported by previous studies. This suggests that conscription not only prepares individuals for military service but also fosters a sense of duty and readiness to defend their nation.

In fact, in the rapidly evolving geopolitical landscape and with increasingly conservative and polarised societies, the importance of value-driven military training cannot be overstated. It goes beyond instilling patriotic fervour and instead cultivates an understanding of the EU as a common good that is essential to protect – along with its core principles of democracy, freedom, justice and human rights. In turn, individuals gain a sense of purpose that transcends national borders and encourages soldiers from different EU countries to work together.

With this in mind, it is no coincidence that Defence and Space Commissioner Andrius Kubilius is expected to work in close collaboration with Executive Vice-President for Prosperity and Industrial Strategy Stéphane Séjourné and, more importantly, Executive Vice-President for Tech-Sovereignty, Security and Democracy Henna Virkkunen.

Legal frameworks can help define these responsibilities, ensuring that individuals understand their role in the collective defence. This includes participating in national service, supporting defence policies and being informed about security issues. Accountability through legal mechanisms and promoting solidarity and cooperation among EU member states is essential for a cohesive and effective defence strategy that reflects its values and commitment to democracy.

The EU’s armies cannot be merely tools of war; they must embody democracies’ defence posture built on a strong bedrock of EU values.

Moreover, conscription can help develop Central European democracies by serving as a unifying force within society. It brings together individuals from diverse backgrounds, promoting social cohesion and a shared sense of purpose. This unity is vital in times of crisis, as it strengthens the collective resolve to defend one’s nation.

For example, there have been many significant examples of women proving their necessity in defence, as in Poland during WWII and the Solidarity movement or the emancipation protests of women in the Hungarian Revolution of 1956. Nevertheless, women’s involvement in the defence sector has been neglected to date, and their roles are traditionally perceived in non-military environments. Including females in compulsory military service is not even considered an option in Central European countries. This is due to various factors, including the lack of adjusted training programs and auxiliary logistics, men-only facilities, societal role perceptions and harassment.

At present, women make up 7% of the Polish Armed Forces, 10% in Slovakia, 13% in Czechia and 20% in Hungary – to meet equal regulations, training, tasks and responsibilities.

Even if societies are not ready, the inclusion of women in at least basic-level training should now be of high priority. A detailed feasibility study should be undertaken by the new Defence Commissioner, in coordination with national armed forces, to assess how the inclusion of women is possible and in what measures and domains it can enhance capabilities. Based on the study, recruitment and programming should then be set in place to meet a minimal threshold of 30% for female participation in each EU army – just as is the case in the business sector.

Such a threshold will allow both equal, democratic access and fill shortages. After all, roles in the armed forces should be determined by ability, not gender. Also, women will share the burdens of war and play an equal part in this horrifying picture – whether at the frontlines or as aides.

Overall, therefore, the EU should adopt a more active role in sponsoring specific policies among Member State armies, in order to foster a more coherent approach to defence. Human resources should be thoroughly audited so as to prepare a revised model of conscription that ensures citizens are prepared to defend their country.

This audit would also help find responses to demographic challenges, lacking female engagement and give grounds to public debate over building resilience capacities and willingness to take up the duty of defending our common good – the EU and its values.

As the EU repeatedly calls for diplomatic solutions, its weakened military capacity risks undermining the credibility of such appeals. The majority of our democratic societies are at present unwilling to take up arms to defend them. Yet the EU’s armies cannot be merely tools of war; they must embody democracies’ defence posture built on a strong bedrock of EU values.

Civil Society Organisations (CSOs) are essential for upholding and developing support for democracy and EU values amongst Central European societies

and citizens. Systemic support for such organisations is key to their perseverance, especially when US public and private democracy support is going to be withdrawn – as is the case with the US Agency for International Development (USAID) and OSF. However, CSOs in countries with autocratic tendencies continue to face obstacles to accessing EU funds. This limits the Visegrád Group’s (V4) participation in EU governance and risks undermining the Union’s treaties and values.

During the previous rule of the Law and Justice Party (PiS), for example, Non-Governmental Organisations (NGOs) in Poland were subjected to political censorship. An analysis by the Supreme Audit Office in June 2024 shows that grants from the largest fund (approximately one billion zloty) aimed at supporting the development of civil society and the National Freedom Institute were allocated ‘in an unreliable, and in some cases illegal, inexpedient and wasteful manner, fraught with the risk of corruption.’

This is reflected in the Civil Society Organisation Sustainability Index (CSOSI), which saw Polish CSOs rise from a score of 2.1 in 2015 to 2.9 in 2022 for overall sustainability. The rule of PiS also saw a rise in CSOs’ financial viability from 3.0 in 2017 to 3.3 in 2022. The index works on a scale of 1-7, from good to bad. The CSOSI paints a similar picture for Hungary, which saw CSOs rise from a score of 2.8 in 2010, when Viktor Orbán was re-elected as Prime Minister, to 4.0 in 2022 for overall sustainability – and from 4.4 in 2017 to 2.8 in 2022 for financial viability. Czechia and Slovakia have seen their sustainability metrics plateau over the same period. For context, the best-performing country for CSOs’ financial viability as of 2022 is Estonia at 2.4.

Signals from NGOs suggest that after the change of the Polish government in October 2023, contact between NGOs and ministries deciding on the distribution of European funds has slowly become more open. However, organisations would expect less formalised meetings and opportunities for practical exchange of experience, as is practised in contacts with representatives of the so-called Norwegian Funds.

The European Commission’s reports on the rule of law in Member States contain many such criticisms of restrictions on NGOs’ freedom of action and access to funding. Of the V4 countries, Czechia and Poland received the best marks in the latest 2024 report, while the worst marks were given to Hungary and Slovakia, where the situation has deteriorated since the Robert Fico government came to power. Nevertheless, issues concerning NGOs occupy a secondary place in this reporting, which is devoted largely to the functioning of state institutions and the fight against disinformation.

There is no mention, for instance, that organisations working on the Polish-Belarusian border had great difficulties in obtaining EU funds – per signals received from NGOs in Poland and reports from the Helsinki Committee for Human Rights. The European Fund for Migration, Borders and Security (AMIF) is worth almost €10 billion – €123 million was earmarked for Poland for 2014-2020 and €237 million for 2021-2027 – but it is estimated that only 9% of the funds are now available to local NGOs. Additional funds are often blocked due to issues with liquidity, formal requirements and complicated procedures.

Such obstacles to access are also apparent in the case of the CERV (Citizens, Equality, Rights and Values) programme – one of the most important instruments for supporting NGOs in the EU. The scheme has been running since 2021 with a budget of approximately €200 million per year (€1.5 billion total), and 173 NGOs in Poland received support of around €12 million in 2021-2022. However, the 2023 EP report on CERV implementation called for an increase in the total budget to €2.6 billion. It also urged the European Commission to ‘simplify the administrative procedures and requirements for re-granting to give organisations applying for re-granting more flexibility.’

A cursory analysis of the projects implemented shows a 60:40 advantage for NGOs from Western Europe. They have more experience in applying for EU funds and more financial resources. They can also count on the support of the EU administration, which, for programmes like CERV, establishes national contact points. Of the new Member States, the Baltics, Croatia, Czechia, Romania, Slovenia and Slovakia have a CERV contact point. By contrast, Poland, Hungary and Bulgaria do not. In the case of Poland, this is a particular omission due to the country’s scale and large absorption capacity.

CSOs in at-risk democracies in Central Europe could either cease to exist, or start undermining EU values should their funding rely solely on autocratic governments or FIMI agents.

This is in line with the lack of a proactive information policy on the part of the ministries coordinating EU programmes and the insufficient involvement of NGOs in consultation processes for fund programming and monitoring committees. It means that, even though NGOs from new Member States have significantly increased their participation in grant applications organised by the EC, their influence on decision-making – in consultations and expert groups – is still much lower than that of Western European NGOs.

Support for Central European CSOs can also be compared to those of the EU Neighbourhood, which receive just as much funding despite not being in Member States. For instance, there are currently 126 grant contracts worth more than €231 million active across Eastern Partnership (EaP) countries, through initiatives like the EU Neighbourhood Investment Platform. The EU Initiative for Financial Inclusion (EUIFI), aimed at fostering MSME growth in the Neighbourhood South (like North Africa and parts of the Middle East), has a total budget of €1.5 billion – blending Commission grants with loans from institutions like the European Investment Bank (EIB) and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD).

All the more closely, European NGO associations are scrutinising the new Commission’s plans for civil society support. In September 2024, Civil Society Europe sent an open letter to Poland, Denmark and Cyprus – the holders of the next three presidencies of the EU Council (EUCO) – as well as Roberta Metsola and Ursula von der Leyen, demanding more emphasis on the public sphere and protection of fundamental rights, against ‘restrictive laws, funding constraints, legal harassment and physical attacks.’

In its October 2024 statement, Civil Society Europe welcomed a new commissioner in charge of democracy, justice and the rule of law (Irishman Michael McGrath) and the task of setting up a permanent platform for dialogue with civil society (Civil Society Platform). However, it warned that such a platform will lack credibility without a real determination from the administration to ‘maintain an open, transparent and regular dialogue with representative associations and civil society’ – per Article 11 of the Treaty on European Union.

In March 2022, the European Parliament adopted a resolution on the limited capacity of civil society and called on the Commission to present a strategy for and index assessing the functioning of the European Public Space. In a letter of March 2022, RARE (Recharging Advocacy for Rights in Europe) network members asked the European Commission to urgently prepare a strategy to counteract funding cuts to NGOs by national governments.

Up to now, the Commission seems to have preferred to develop dialogue with the public through major events, like citizens’ panels at the recent Conference on the Future of Europe. These are supposed to discuss ‘political’ topics with conclusions then fed into Commission work. However, such formats follow formal, rigid patterns designed by large, most often Western European communication agencies – traditionally the winners of the tenders organised for this type of activity.

Also, randomly selected citizens, under the guidance of experts and moderators, prepare many recommendations that are important and interesting, but potential criticisms of EU institutions are toned down. Choice of topics is also questionable: the key subject of institutional reform was excluded from the discussion at the Future of Europe Conference.

Similar issues are identified with public consultations organised by Commission Directorates, which are highly formal and do not provide adequate time for NGO experts to be heard. There is also still no proper, official channel of communication between the Commission and NGOs – through which they can raise issues like insufficient access to EU funds managed by national governments, slander from national governments, or report their participation to expert groups. These problems are more often raised in meetings organised by Commission Representations in Member States for visiting officials.

Unfortunately, Ursula von der Leyen’s first speeches after re-election, as well as the division of tasks within the new EC, do not indicate there will be a significant increase in the position of NGOs in the legislative process of the EU, or stronger monitoring of national government actions towards NGOs.

Moreover, commission guidelines for 2024-2029 focus much more on strengthening competitiveness. The chapter on strengthening democracy is in the background, and support for NGOs is limited to two sentences: promising to intensify cooperation with organisations ‘that have the expertise and an important role to play in defending specific societal issues and upholding human rights’ and a commitment to ‘work towards greater support for NGOs in their work.’

If it remains challenging for V4 CSOs to secure funding and actively participate in the Commission’s decision- making process, the EU may fail to meet its Strategic Agenda objective of establishing a strong and democratic Europe. Consequently, CSOs in at-risk democracies in Central Europe could either cease to exist, or start undermining EU values should their funding rely solely on autocratic governments or FIMI agents.

In her May 2024 speech, European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen outlined the need for a ‘European Democracy Shield’ to counter FIMI (Foreign Information Manipulation and Interference).

Currently, the European Union External Action Service defines FIMI as ‘a pattern of behaviour that threatens or has the potential to negatively impact values, procedures and political processes. (…) Actors of such activity can be state or non-state actors, including their proxies inside and outside of their own territory.’

In turn, the EU approach to countering malign influence focuses on foreign agents, overlooking domestic actors who, while not necessarily proxies, still promote anti-democratic rhetoric among citizens. Often, this fails to provide a democratic shield against but rather empowers national policies that pressure Civil Society Organisations (CSOs) – which are essential in combating disinformation through de-bunking, pre-bunking and media literacy campaigns.

The Commission likely focuses on foreign sources of disinformation because a more prescriptive approach from supranational institutions could fuel narratives by non-democratic actors in the region, who claim the EU is infringing on their ‘sovereignty’.

Recent elections in Moldova and Georgia highlighted notable instances of election interference, including vote-buying, ballot-stuffing and disinformation campaigns warning of potential war with Russia if pro-EU choices prevailed. In both countries, however, pro-Russian factions – such as the ruling party in Georgia – accused the West of interference.

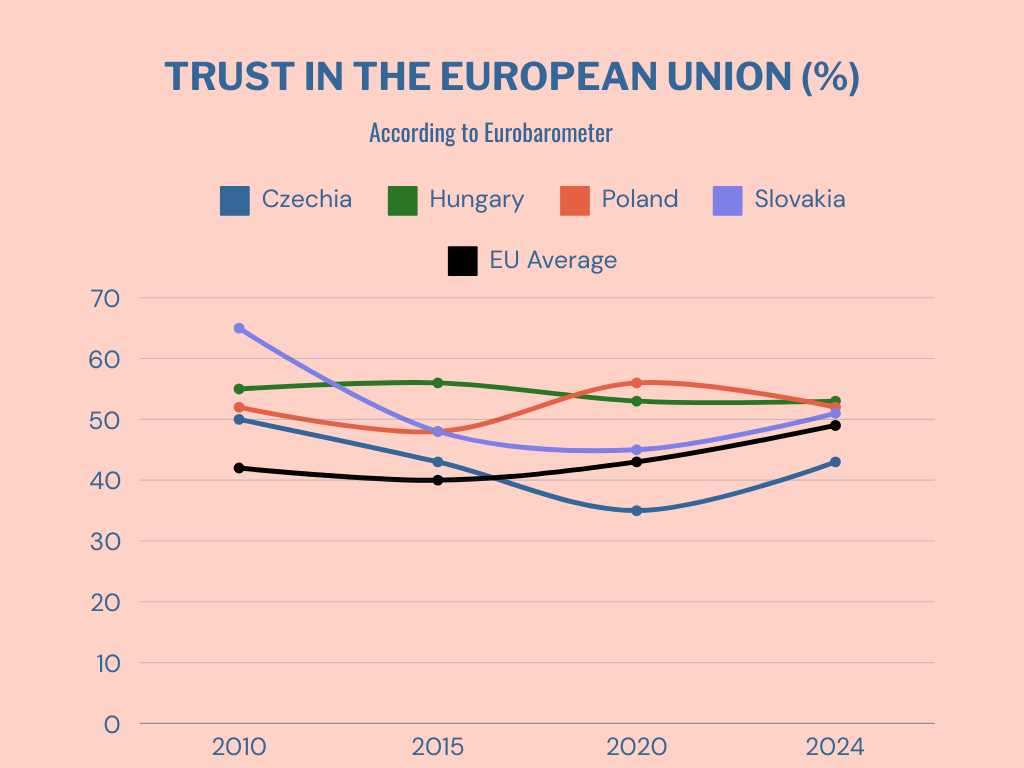

Yet far more important is that EU institutions are often perceived more positively in Central Europe than national governments. Executives should leverage this positive perception through clear, accessible, strategic communication campaigns, rebuilding confidence in democratic institutions while leaving less room for malign domestic actors to exert their influence. This is in line with the Strategic Agenda for 2024-2029 and the need for the EU to counter domestic disinformation or derogatory speech against CSOs in public.

We propose that campaigns could take place within a redirected, more inclusive framework: DIMI (Democracy Information Manipulation and Interference). The EU should at once stress its core values (Respect for human dignity, Freedom, Democracy, Equality, Rule of law, Respect for human rights, including those of minorities) as well as reaffirm its support for pro-democracy CSOs and movements, even those funded by Western – though non-domestic – sources.

Observe the example of Slovakia. In July, the Commission warned Bratislava that it could face legal action if it proceeds with a proposed law requiring NGOs with foreign funding to label themselves as ‘organisations with foreign support.’ This echoed a previous conflict with Hungary, which enacted a similar law in 2017 only to repeal it in 2021 following an EU court ruling. In response to further criticism of the EU’s rule of law report, Prime Minister Robert Fico argued that any issues stem from EU pressure over foreign policy – even though the report includes non-binding recommendations for all 27 EU member states.

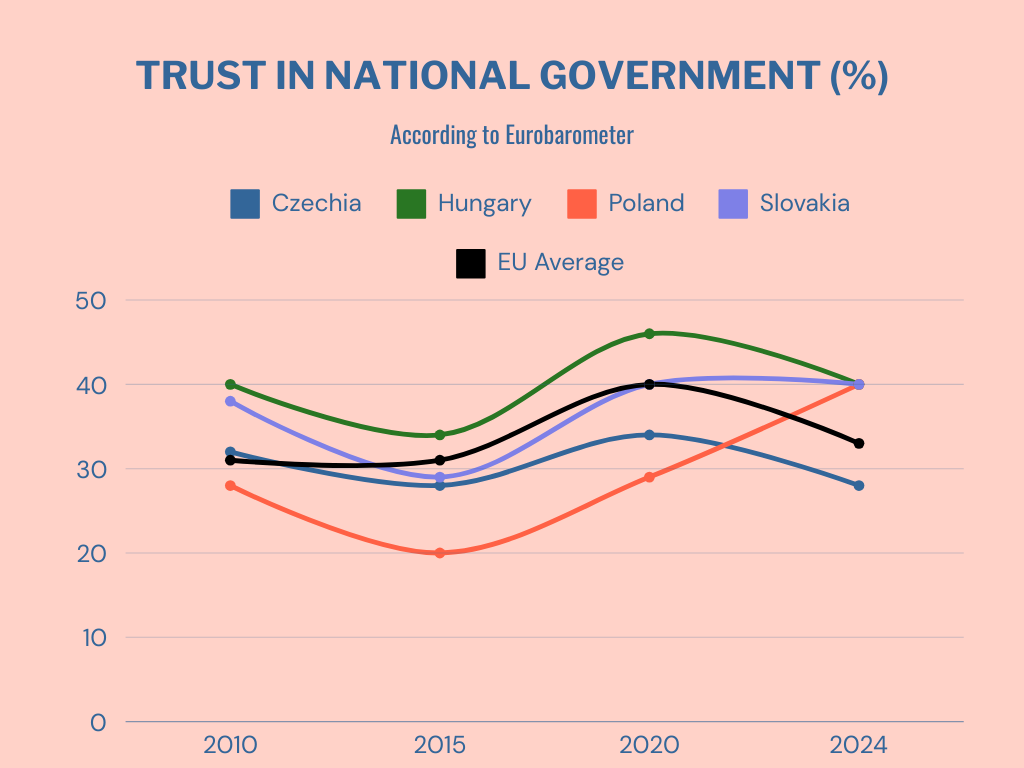

This is a clear example of the narrative on EU overreach that malign domestic actors can put forward. Yet, the efficacy of anti-EU rhetoric should not be assumed. In Central and Eastern Europe, public trust is often split between national and supranational institutions. In Slovakia, 40% of citizens trust in the government, while 51% trust in the EU, creating a climate of distrust that can allow disinformation to thrive: the 2024 European elections saw Slovak populist parties advance false claims, like that the EU is forcing citizens to eat ‘contaminated Ukrainian wheat.’ A transparent, proactive approach, however, could leverage greater trust, counter scepticism and debunk narratives on foreign imposition.

As the Commission develops its FIMI policy framework, it should also prepare to protect CSOs from domestic discrimination, misinformation and legal or bureaucratic malpractice.

In Poland, 88% of Poles back NATO membership and 52% have trust in the EU, but only 40% have trust in the national government. Such persistent low-level trust is conducive to disinformation, exemplified by populist narratives emerging during election periods, and a further 39% of Poles report dissatisfaction with democratic governance. Counter-DIMI communication should focus on security as a mutual interest between the EU and Poland and address perceived sensitivities around overreach.

In Hungary, while 53% trust the EU and 63% view NATO favourably, satisfaction with democratic governance stands at just 49%. Disinformers also exploit Euroscepticism while stirring nationalist sentiments. The EU should promote a balanced view of European policies without appearing overly critical of Hungary’s domestic concerns.

In Czechia, while 43% of Czechs trust the EU and 73% would vote to stay in NATO, EU approval has declined due to ‘dictate from Brussels.’ Recent domestic campaigns saw false claims about EU regulation threatening local industry, and a third of Czechs are now also more open to authoritarian governance. A DIMI-focused approach should emphasise democratic values and policy transparency to reduce scepticism.

This is in line with the lack of a proactive information policy on the part of the ministries coordinating EU programmes and the insufficient involvement of NGOs in consultation processes for fund programming and monitoring committees. It means that, even though In these ways, through the DIMI framework, ‘The EU must urgently develop more effective strategic communication that takes into account local contexts, allocates more resources to civil society and independent media and evokes emotional responses in stakeholders,’ explains a Visegrad Insight Fellow from Slovakia.

Importantly, in conjunction with disinformation campaigns, CSOs also face increasing pressure from administrative harassment, frivolous litigation (SLAPPs) and funding cuts. This is why the EU DisinfoLab has called for increased financial support for civil society and independent media, highlighting the urgent need for an emergency legal fund to combat strategic lawsuits and a dedicated budget for counter-disinformation efforts.

This could run in tandem with the Anti-SLAPP Directive, which came into effect in May 2024 to protect journalists and human rights defenders from abusive court proceedings, as well as the Coalition Against SLAPPs in Europe (CASE) – an organisation that offers help to those facing SLAPPs. The legal fund would be particularly useful given that the Anti-SLAPP

Directive requires national governments to enact its legislation and so can ultimately prove ineffective, as the countries where it’s needed most are often led by parties that (indirectly) benefit from SLAPPs.

It is also important to highlight that such scenarios apply to all of Central and Eastern Europe. Malign domestic and foreign actors seek to exploit regional vulnerabilities, foster societal division and destabilise public trust in democratic institutions. For instance, in the Black Sea, disinformation targets government institutions, framing the West as an enemy; in the Baltic states, Russian-controlled media amplifies polarising narratives, particularly among the Russian-speaking population; in the Western Balkans, disinformation is weaponised during election periods to manipulate public opinion and consolidate political power.

Despite these challenges, CSOs play a crucial role through initiatives that improve media literacy, conduct fact-checking and educate citizens about digital security. Notable examples include Romanian CSOs addressing public health misinformation during the COVID-19 pandemic; Lithuanian organisations implementing innovative media literacy programmes in partnership with tech companies; Polish CSOs providing support to Ukrainian war refugees.

86% of citizens say it is important that media and CSOs in Member States can operate freely and without pressure, even when they are of a critical perspective. As the Commission develops its FIMI policy framework, it should also prepare to protect CSOs from domestic discrimination, misinformation and legal or bureaucratic malpractice. Moreover, the EU could use its more favourable position in these countries to reaffirm support for CSOs that receive funding from the EU, Nordic countries or other Western institutions.

Without this shift in strategic communication strategies and core funding as well as shield funding, foreign and domestic malign influence will continue to expand its tactics, leading to the erosion of trust in all democratic processes. The EU must support its CSOs, so that citizens are not just defended from autocratic actors but believe in shared EU values and the defence and development of their democracies.

In this 3-year long project, Visegrad Insight – Res Publica Foundation aims to promote democratic values in Central European states through our dedicated framework, involving civil society actors and policy leaders in strategic foresight work that addresses policy questions relevant for strengthening the Union’s democratic security.

This project aims to elevate the quality of public and expert-level debate on the future policy directions in the EU in the context of democratic security and common EU values while nurturing collaboration amongst civil society as a means further to embed democracy and its resilience in the region.

We engage in activities such as scenario-building, yearly foresight reports, conferences and media appearances to improve discourse on EU values and foster collaboration within civil society. Leveraging our position, Visegrad Insight drives a CEE-wide public foresight debate on future scenarios for democracy, freedoms, elections and social cohesion, bringing together thought leaders, academia and policy-makers. Our primary goal is to address the decline in public debate caused by a lack of information sovereignty, limited trust in democratic institutions and political polarisation, offering solutions and reinforcing support for democratic values.

In 2024, our foresight work centred around the following three main topics:

The outcomes of this research and consultation are presented in this report.

This project is based on the following regular activities:

Wojciech Przybylski – EU Values Foresight project lead

Staś Kaleta – Co-author of the report

Magda Jakubowska – Author of Foster Societal Readiness for EU Armies

Marzenna Guz-Vetter – Author of Boost CERV Funding in At-risk Democracies

Galan Dall – Author of A Shield for CSOs: Countering Malign Foreign and Domestic Actors

Magda Przedmojska – Project Management

This project is supported by the 4-year European Commission’s Europe for Citizens Programme and the Citizens, Equality, Rights and Values Programme (CERV) framework cooperation.

Funded by the European Union. Views and opinions expressed are however those of the authors only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union. Neither the European Union nor the granting authority can be held responsible for them.

Navigate to:

EU Values Foresight Homepage

How European Democracies Are to Survive a New Trump Age – 2023 Report

Horizon Scanning

Events