26 March 2019

An informative look at the world and tactics of those spreading disinformation and discontent as well as the institutional and private resources fighting against these disruptive forces.

[ihc-hide-content ihc_mb_type=”show” ihc_mb_who=”reg” ihc_mb_template=”3″ ]

The following article acts as a guide to understand more about the elements of trolling and use of bots – for better or worse – in the digital space.

Internet bot is an automated computer program intended to perform certain tasks online instead of a human being.

| Good bots | Bad bots |

| – search engine bots | – impersonators |

| – commercial crawlers | – scrapers |

| – feed fetchers | – spammers |

| – monitoring bots | – hacker tools |

A great majority of bot-generated internet traffic comes from those meant to mimic human behaviour. This enables them to assume a fake identity and influence real human beings’ opinions and decisions. We can detect them based on their simple limitations:

Trolls – individuals engaging in trolling, which can be defined as making comments intended to provoke conflict. In psychological research, trolling is described as a psychological dysfunction related to personality traits.

In a hybrid and state-sponsored war, one can distinguish between “classic trolls”, which pursue their own interest solely to sow discord and instigate conflict within the online community, and “hybrid trolls”, which are used as an information warfare tool by state entities.

Both bot and normal ad activities are based on algorithms which use online platforms to strengthen and facilitate online content distribution.

Bot- or troll-based activities can be run by state or private entities, or by third countries and can be combined to achieve shared goals.

In addition, they are amplified by botnets (a number of connected devices all running several bots for specified, harmful purposes such as Denial of Service (DDoS) attacks, phishing, spam messages, ransomware, click fraud, etc.) and collective trolling activity.

Examples of disinformation against Europe using the aforementioned tools and focusing on the most topical political developments and social issues are readily available.

A good example would be the so-called “yellow vests” protests in France where an analysis of developments and online activities shows classic disinformation measures in the social media consisting in promoting content from Russian language media with the hashtags #giletsjaunes #yellowvestes from fake Twitter accounts, which, according to French law enforcement services, sent 20 thousand fake news accounts about the protests. The purpose was to amplify the message of the prevailing chaos and to show the West in a bad light.

Similarly, during the Bundestag election in Germany, a country characterised by political stability, heightened activity was observed from AFD’s network where anti-immigrant content grew in quantity in social media using Russian language bots. In addition, the Russian platform Vkontakte (VK) got involved in the process, supporting the AFD message, and attacking Chancellor Merkel for her attitude towards refugees and showing them as a threat to Germany.

The attempts to exert pressure on the German election were less pronounced than those focused on the French presidential election. There, bots were used on a large scale in promoting #MacronLeaks and the related content, which on the eve of the election engaged nearly 100 thousand users.

Evidence indicates that during the referendum in Catalonia 87% of the 65 accounts that shared the most RT and Sputnik content about the independence of Catalonia were automated. More than 78% of the news items defended the independence of Catalonia and presented the Spanish state as repressive and using brutal police behaviour.

The disinformation efforts undertaken may vary depending on the country, but they mainly involve interference with democratic processes and are aimed to:

Disinformation campaigns carried out by third countries are an element of hybrid warfare, which consists in combining the spreading of fake news and media spin with cyber attacks and hacking of networks.

In our part of Europe, efforts to disinform are undertaken mainly by means of websites and on social media. We can find shared topics and narratives for the entire region, which are subject to disinformation efforts. These include:

In Czechia, disinformation campaigns are forcing false narratives about refugees, the Islamisation of Europe, crimes committed by refugees, the war in Ukraine and showing EU political elites and institutions as weak and divided.

In Slovakia, disinformation efforts can be also found with respect to the wars in Ukraine and the Middle East – especially operations in Syria – with more general falsehoods being spread about the European Union, EU elites and institutions.

In Hungary, these involve mainly anti-immigrant, anti-European, anti-NATO, anti-American and anti-Ukrainian content that also shows Ukraine as a weak and badly governed country in turmoil. Moreover, one can also find attacks on liberal values and NGOs that promote them.

In Poland, a narrative about Polish-Ukrainian relations is mainly spun, heating up the conflict over historical issues as well as a concerted attack against the EU and its institutions, with additional emphasis on denigrating Western values.

As evidenced by the above, there are topics shared by the entire region, which are subject to disinformation efforts: European Union, EU institutions, EU political elites and war in Ukraine.

The set of measures aimed to counteract manipulation and disinformation during the electoral processes (national and European elections) have been the object of many discussions with member states.

In its efforts, the EU has also taken into account cooperation with NATO and the G7. A key role in the process of counteracting disinformation to defend democratic systems is to be played by civil society and by online platforms – especially social media – which have become the major channels for spreading disinformation.

This phenomenon has reached a global dimension during the presidential campaign in the US, where fake news garnered the highest user engagement on Facebook. However, the largest online platforms – Facebook, Twitter, Google, YouTube – have developed and adopted self-regulatory measures.

Under the rather straightlaced moniker, this Code of Practice on Disinformation in effect in the EU deals with online transparency: labelling advertisements sponsored by political parties, identifying and closing down fake accounts and protecting citizens’ data, especially in the context of European Parliament election.

Disinformation uses cutting-edge technologies and tools which change fast and that is why institutional measures adopted by the EU and member states must evolve just as rapidly while using the latest technologies. These measures must be also based on close collaboration between member states and EU institutions.

[/ihc-hide-content]

_____

About:

About:

Visegrad Insight 2 (14) 2019

European Parliamentary #Futures

Download the report

Published by Res Publica Foundation

Partner: Konrad Adenauer Foundation

Supported by: ABTSHIELD

Authors:

Wojciech Przybylski, Editor-in-Chief

Marcin Zaborowski, Senior Associate

Team:

Magda Jakubowska, Director of Operations

Galan Dall, Managing Editor

Anhelina Pryimak, Editorial Assistant

Anna Kulikowska-Kasper, Contributor

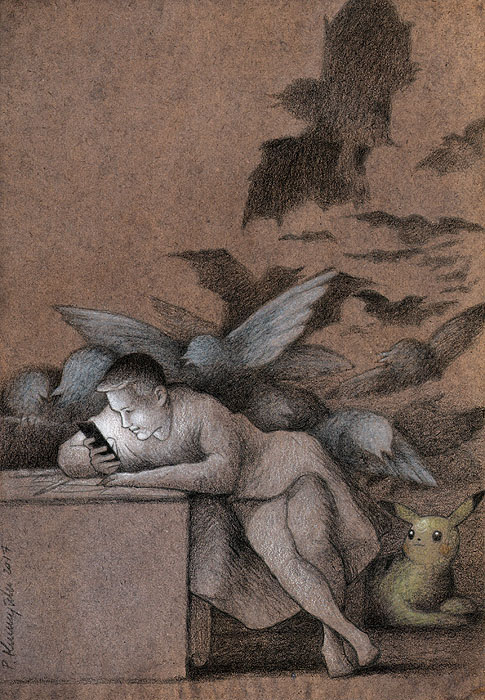

Paweł Kuczyński, Illustrations

Rzeczyobrazkowe, Graphic Design